OPTIMUM HPGR PERFOR MANCE IN CLOSED-CIRCUIT OPERATION

In tertiary applications, HPGRs have to be operated in closed circuit. Consequently, the ball mill feed is not the “discharge” of the HPGR but is the product of the size distribution of the HPGR discharge and the mesh size of the closing screen. This raises two questions: first, what influence do HPGR operating parameters have on the feed-size distribution to the ball mill; and secondly, what is the most efficient way to operate an HPGR?

In open circuit, the operating parameter that manifests the most influence on the particle-size distribution is the press force applied to the rolls. The energy absorbed by the material has been shown to be proportional to the applied press force.

In a closed circuit, however, the influence of the press force on the product size of the circuit is lost. This is demonstrated with two examples, one taken from tests on a semi-industrial scale unit and the other from tests on a laboratory-scale HPGR

Results were taken from single-pass tests on these units, in order to prove that the findings were independent of the machine size.

The press forces applied were in the range of 2.7 to 4.3 N/mm2 on the semi-industrial unit, and from 2.3 N/mm2 to a higher value of 8.4 N/mm2 on the laboratory-scale unit. The impact of the press force on the throughput and energy consumption of the circuit are also shown.

A screen undersize, representing the circuit product, was calculated on the basis of 100% screen efficiency from the discharge. Cut sizes were 4 mm for the semi-industrial circuit and 1 mm for the laboratory-scale circuit. It was assumed that the recirculation of screen oversize did not affect the size reduction in the HPGR significantly. On this basis, a projection of the circuit performance in terms of throughput and energy consumption was also made. This approach may be considered simplistic but is adequate to explain some of the principles.

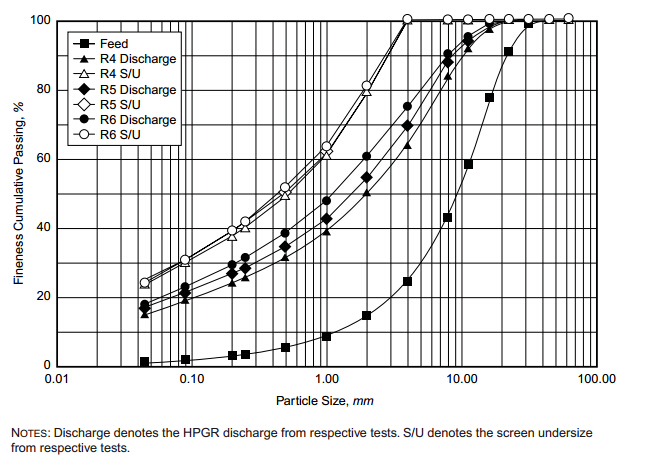

Figure 6 shows discharge size distributions of a copper ore treated in a semi-industrial test unit. The grinding force was steadily increased from test R4 to R6, resulting in a finer discharge. The circuit product of an HPGR with a 4-mm classifying screen was cal- culated on the basis of 100% screening efficiency.

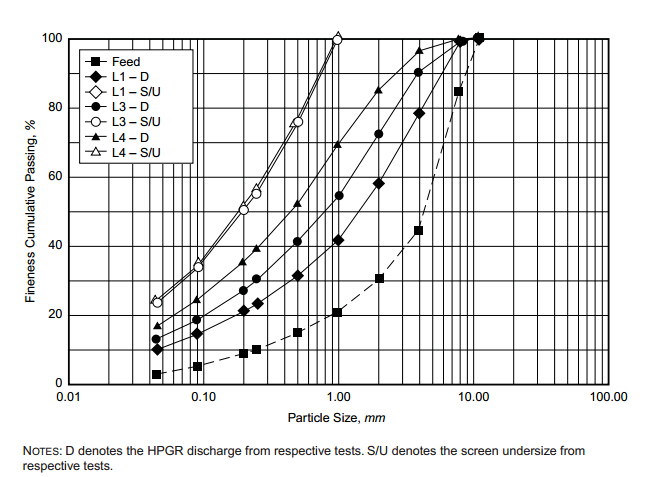

Figure 7 shows discharge size distributions of a platinum ore treated in a lab-scale test unit. The grinding force was steadily increased from test L1 to L4, resulting in a finer discharge. The circuit product of an HPGR with a 1-mm classifying screen was calculated on the basis of 100% screening efficiency.

The conclusions drawn from Figures 6 and 7 were that the size distribution of the final circuit product did not vary much, no matter if the HPGR discharge was finer or not. The fineness of the circuit product was largely determined by the mesh size of the closing screen.

However, the applied press force had a strong influence on the circulating load and the circuit throughput with an HPGR of given size, as well as on the energy consumption, as shown in Figures 8 and 9.

In Figure 8, the specific energy input was increased by 30% while the throughput of the closed circuit increased by only 10%. In Figure 9, the specific grinding energy was increased even further by 100% to 8.2 N/mm2, whereas the throughput of the closed cir- cuit only increased by 40%. These examples show that operation at high specific press forces, 8 N/mm2, reduces energy efficiency drastically.

The following general conclusions were drawn with regard to optimum operation of HPGRs in closed circuit:

For harder ores, increasing the press force increases the circuit throughput, but the increase in energy consumption is disproportionately higher.

For softer ores, increasing the press force may even decrease the circuit throughput. The additional fines produced do not compensate for the loss in specific throughput of soft ores resulting from the reduction in the operating gap.

Optimum grinding forces are material specific. Specific grinding forces up to 8 N/mm2, such as those applied in cement grinding, are unsuitable for minerals applications where the final product fineness is substantially coarser.

Circuit throughput can be adjusted by varying the applied press force. The increase in the energy consumption, however, is often disproportionate to the increase in throughput, and varying the roll speed is a far more efficient means of adjusting the circuit throughput.

These considerations still leave open the question as to what impact the application of higher press forces may have on the energy requirements in downstream ball milling. This issue is addressed in the next section.

Get Detail Information:

(If you do not want to contact to our online customer service, please fill out the following form, Our client manager will contact you later. We will strictly protect your privacy.)